For Mature Audiences Only

Shakespeare Is Not of An Age but for All Ages;

Kids Dig Him, Too

We heeded the warning: “For mature audiences only.” The Alabama Shakespeare Festival in 2000 set its production of The Comedy of Errors in South Beach Florida, and it promised to be rather racy. Sarah and I decided that it might not be appropriate to take my sons to that one—Jonathan was then 13, Ian 11—so, when we adults headed into the theater to see Comedy, we sent the boys into another of ASF's theaters to see King Lear instead.

I'll give you a moment to let that sink in.

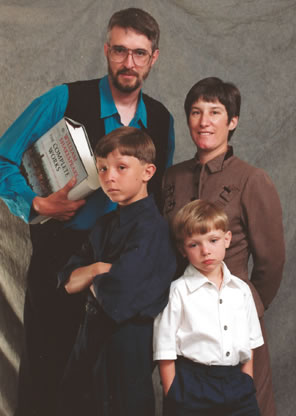

Oh, the tragedy: Eric and Sarah with Jonathan (past and present actor) and Ian (Hamlet).

I'll give you another moment to question my fitness as a parent, too. Instead of exposing my tween children to “racy,” I let them watch a man get his eyes gouged out. Even my two sons to this day find that a bit weird. With the advantage of a dozen years' hindsight, I might have done things differently. For one thing, King Lear is my favorite Shakespeare play, so why did I pass that up, especially with my sons? Also, Comedy was racy by Alabama standards, which is merely flirty in most other places; the animated Ice Age films contain more innuendo. But at the time—ah, who am I kidding? Even now, the South Beach Comedy sounds more intriguing and enticing than the more traditional staging of Lear, especially with that “for mature audiences only” tag. What (then) 42-year-old—or (now) 54-year-old—wouldn't choose racy fun-in-sun over eye-gouging nihilism?

We'll set my parenting choices aside for now, though, because some readers might not have even made it that far in the above scenario: they are stuck on the fact I let my 13- and 11-year-old sons go into a theater by themselves. Not only that, it was a Shakespeare production. Why would I take (expose, subject—insert your own judgmental predicate here) a 13-year-old and an 11-year-old to a Shakespeare play at a grown-up theater?

The answer is simple: I had been doing so since they were 7 and 5. Their first live Shakespeare was Hamlet at the American Players Theatre, in Spring Green, Wisconsin. We chose that particular outdoor theater because we thought the setting would keep them entertained if the play did not (why that play, though, I have no idea—even I, looking back, can only ask, What was I thinking?). I also gave them fair warning of how they would have to behave and made sure we sat near the back in case I needed to make a quick exit with a son in tow. That latter precaution was unfounded; my kids were well behaved the whole time. They knew they were privy to a grown-up experience. And, as it turned out, they were mesmerized by the play. Ian even play-acted Hamlet in our neighborhood playground in the weeks after.

The impact on Jonathan was much deeper as he ended up pursuing a career in theater and theater education. When he was cast in the Hudson Warehouse production of The Comedy of Errors this summer, he was not only excited to land his first Shakespeare role in a New York company, he was more enthusiastic about the fact that it would be an outdoor production at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Riverside Park. His first theatrical experience in his childhood was Shakespeare at an outdoor theater, and now he was realizing his childhood dream to some day play in such a production. (By the way, he's currently in the Hudson Warehouse's production of Richard III, which we'll be seeing this weekend.)

I do not consider my sons extraordinary, beyond what a parent is contractually obligated to feel about their children. But their behavior in the theater and their grasping Shakespeare at such a young age, I see as nothing extraordinary at all.

Let's address the former first: behavior. Certainly, Sarah and I coached Jon and Ian before that first play (and we have that good-cop/bad-cop thing going, you know: daddy or wicked stepmother). Kids who understand and respect discipline can be coached, and, just as important, they generally respect privilege, too; kids always want to sit at the adult table in the dining room instead of being stuck with the other children in the kitchen. When I was in first and second grade we lived in Ankara, Turkey, and my parents regularly attended the symphony and opera, often taking my two older brothers (my brothers and I are all spaced three years apart). Finally, I was allowed to join them. I distinctly remember my first time, and it was my middle brother, John, who coached me on behavior, telling me that people weren't even allowed to cough while the orchestra was playing. I had never needed to cough so badly as I did that night, but I managed to stifle all coughs because I didn't want to risk punishment at the hands of either Mom or Dad or miss out on future concerts.

Besides, in my defense for taking a 5-year-old into a theater and sending a 13-year-old along with his 11-year-old brother into a theater without parental supervision, I offer a two-word rebuttal: cell phones. I strongly believe theaters should enforce age bans, not on children 15 and under but adults 60 and over who don't know how to turn off their friggin' mobile phones. Furthermore, anybody 18 and over who believes their calls (even on vibrate) trump their fellow patrons' theatrical experiences should be banned from all theaters and concerts for life. I attended a student matinee of A Midsummer Night's Dream at the American Shakespeare Center's Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia, and when in the pre-show the audience was instructed to turn off their cell phones, a hundred young teens rolled their eyes but took out their phones and shut them off. When will adults learn to do as they are told? Cell phone etiquette is fodder for another commentary, but I offer it here as an example of how age is a lesser factor in theater behavior than the individual's discipline and social acuity. If unsupervised 10-year-olds are sitting in front of you and a couple in their 60s is sitting behind you, my money is on the people behind you causing more distractions; the kids are far less likely to comment on the action during the play, ask “what did he say?” and get a loud reply drowning out for the rest of us the next line, or answer their phones and texts and shoot a photo.

Still, will kids sit through Shakespeare? Was Ian at 5 years old so brilliant he understood Hamlet? Most kids would be bored to tears, right? Heck, most adults claim to be bored to tears by Shakespeare, and so they are certain that their kids would be, too, because their kids are reportedly not as smart. Full disclosure first: Yes, Ian was and is brilliant. But he was not exceptional in “getting” Shakespeare, and exhibit one was across the bedroom. Jon had difficulty with grades in school, but he got Shakespeare, and his appreciation of the theater we exposed him to inspired him to get a bachelor's degree in theater; brilliance achieved. I've also seen other kids at Shakespeare plays, and they gobble up not just the action but the words, too. You can see it in their reactions. Part of this is due to the skills of the actors and the nature of the productions; but, then, well-presented Shakespeare can even turn those “bored-to-tears” adults into Shakespearean disciples.

Nevertheless, the real credit goes to Shakespeare himself. When I was a freshman at the University of Missouri, I wrote a story for the campus newspaper profiling the university's lab school. I interviewed third- and fifth-graders, and as part of their curriculum they were studying Shakespeare and French, too. Studies have long shown that the younger you are, the more easily you can learn a foreign language, so these third graders spoke French well, and the fifth graders talked circles around me about Twelfth Night. At the time, I was still new to Shakespeare, but I had at least seen that play, and I didn't get Viola's nuanced verses the way these children did. Even if a 5-year-old doesn't fully comprehend Hamlet—on the playground Ian certainly was butchering the verse—a child can still appreciate Shakespeare's wordplay and verse structure. If Dr. Seuss had illustrated some of Hamlet's lines it would have been a children's classic; to whit: “To be or not to be,” “the play's the thing wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king,” “sweets to the sweet,” “very like a whale,” “a little more than kin and less than kind” (even I don't know exactly what that last one means, but it sounds fun). Kids have been reciting the witches' lines in Macbeth as often as they describe London Bridge falling down or a woman living in a shoe.

Ah, the comedy: "Let's not look so glum this time," the photographer said.

For this reason, I believe parents—and theaters, too—should expose children to pure Shakespeare whenever possible, and not just some kid-friendly version, either. The plays' plots are not necessarily the be all and end all for kids, which is what the Lambs believed when, in the early 19th century, they turned Shakespeare's plays into children's bedtime stories. Certainly, experiencing Shakespeare's plots for the first time can be entrancing, as long as there is a plot. But even something like Measure for Measure could have relevance. That last scene where the Duke reveals himself is a gotcha moment that was similar to the plots of many of my daydreams growing up (which may be why I like that play so much).

Nevertheless, it is Shakespeare's language, archaic as it may be to many adult ears, that has magical properties for children. And don't think that kids understand it less than we adults do. Elsewhere on this site I've written about the little girl attending As You Like It at the Blackfriars who reacted with indignity to one of Rosalind's lines insulting women. That little girl got it without any help from a parent; vice versa, in fact, because only when the girl reacted did other audience members get the joke.

Let's be clear, I'm not advocating that every kid, from toddler to teen, should be allowed to attend the theater. Children must know discipline and must be socially aware before they should be allowed in a theater (frankly, I'd lay the same condition on all people if I could, not just the under 18s). If after a couple of experiences they don't like it, don't force-feed them (that's true of anything; I tried to ram baseball down my sons' throats and, well, the Shakespearean Jonathan now avoids baseball like the plague). And, back to the beginning of this commentary, be wise in what plays and productions you take your children to. Titus Andronicus is an R-rated play, period. King Lear and even some Macbeths I've seen could give kids nightmares. My overall point here is don't underestimate the ability of children under 18 to not only appreciate the theater, but also comprehend and appreciate Shakespeare, as written.

In hindsight, our mistake there at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival was not decreeing that my young sons would see the eye-gouging Lear on their own instead of the racy Comedy with us. Rather, my parenting skills come into question in that Sarah and I selfishly chose not to see Lear with the boys; we thereby missed out on a family Shakespeareance. Those are the best kind.

Eric Minton

August 31, 2012

A Note from Ian

I read your article—good stuff.

I'm surprised that nowhere did you mention how we'd seen most (if not all) of the BBC Shakespeare: The Animated Tales series. That, in and of itself, was remarkably beneficial to not only understanding Shakespeare but also appreciating him. From popular (Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet) to lesser-emphasized plays (As You Like It, The Winter's Tale); from light-hearted (Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night's Dream) to bloody (Richard III, Othello, Macbeth), Jonathan and I were given the right kind of introduction to what Shakespeare is all about. Similar to your idea of a Dr. Seuss-illustrated Shakespeare, The Animated Tales was captivating, in a medium that kids could appreciate, and used much of the same language as the plays themselves. Throw Robin Williams into the mix from the HBO re-airings and it was wildly appealing. To this day it's one of my favorite children's programs. In fact, anybody who claims to not "get" The Tempest, I simply show them the animated version on YouTube and suddenly they have a new respect for the play.

Also, I think it's funny that you mentioned Titus Andronicus as an R-rated play as I had read it in the fifth grade and been using it for various book reports all the way through high school. It was even the first R-rated movie that I actively snuck in to watch well before any of my parents would let me. A transgression, I know, but it was in the names of Shakespeare and good filmmaking. Besides, well before Titus we had seen Macbeth's "bloody baby" on-stage and in the Stratford, Canada, wardrobe [during a backstage tour], so I considered myself justified in my desensitization to Shakespearean violence.

Ian Minton

September 6, 2012

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances