All the Way

LBJ's Knife Fight: Where Words Are Blades,

and Will Changes the Tide

By Robert Schenkkan

Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Angus Bowmer Theatre, Ashland, Ore.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012, L–8&10 (middle stalls)

Directed by Bill Rauch

Few writers could craft better dialogue than Lyndon Baines Johnson naturally spoke. Few lists of dramatis personae could match the real characters making headlines in 1964: Martin Luther King Jr., J. Edgar Hoover, Hubert Humphrey, Bob Moses, George Wallace, Lady Bird Johnson, Roy Wilkins, Richard Russell, Everett Dirkson, Ralph Abernathy, Strom Thurmond, Robert McNamara, Stokely Carmichael. Few fictional plots could be as dramatic as Congress passing the Civil Rights Act and the integration of the Mississippi delegation at the National Democratic Party Convention.

Lyndon Johnson (Jack Willis) and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (Kenajuan Bentley) argue about voting rights as David Kelly, Daniel T. Parker, and Derrick Lee Weeden wait and watch in the background in the Oregon Shakespeare Festival world premiere of All the Way. Photo by Jenny Graham, Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

However, few playwrights could so successfully craft such reams of history into three hours of riveting theater. Robert Schenkkan accomplishes that, and with Bill Rauch's dynamic directing and a cast of 17 splendid actors playing 39 roles, All the Way, making its world premiere at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, is not only Shakespearean in scope but in quality, too.

As a student of Martin Luther King Jr., I've read Taylor Branch's three-volume historical tome on King and the civil rights movement, and in reading Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–1965, I came to appreciate both President Johnson's tenacious drive to achieve racial equality in America and his peculiar personality. This was a man who got in the face of his mentor, Sen. Russell, a father figure to Johnson, and warned him that if he stood in the way of the civil rights act, "I'll crush you" (a conversation that gets into Schenkkan's play). I went into OSF's Angus Bowmer theater with high expectations; Schenkken, Rauch, et al., exceeded them. Afterward, I asked my wife, Sarah, what she thought of the play. "It was perfect," she replied.

What makes it so is that this production scores one hundred percent in four aspects. First is the subject matter. Legislation and party politics may not sound like exciting drama, but Johnson likened politics to a knife fight, and he was Bourne-like in the way he maneuvered the Civil Rights Act through Congress. Then, black leaders upped the tension and handcuffed Johnson politically when the Mississippi black delegation tried to crash the Democratic Convention. Action thriller heroes would use combat skills or gadgetry to extricate themselves from impossible jama; Johnson only had his wits and words as his weapons.

Just as Shakespeare's Henry VI political tragedy and Henry V warrior biopic are relevant to today, this more recent history is not only relevant, it directly factors into what is playing out on the political scene today. Johnson's actions forever changed the alignment of the Democratic and Republican parties, and today's presidential political debate is grounded in the sea-change policies and programs Johnson pushed through.

Second in making this production perfect is the script, and with real characters like those portrayed in All the Way, they were bound to speak lines that are funny, profane, profound, and downright dangerous. Much of the dialogue is drawn from actual rhetoric picked up from speeches and wiretaps, including Johnson's own bugged Oval Office meetings and phone calls. Here are just a few laugh-garnering gems:

- King quoting Roy Wilkins on the original civil rights bill of 1957: "Said that bill was like soup made from the bones of an emaciated chicken which had died of starvation."

- Johnson on Hubert Humphrey: "He's nice. Nice is what you call a girl with no [breasts] and no ass and no personality."

- Lady Bird Johnson after Walter Jenkins, the president's closest aide, tells her she looks beautiful: "No, I'm not. But I work hard with what I have and that's all a body can do."

- Johnson to George Wallace: "If you think helpin' to elect a whole buncha Republican legislators in Alabama is gonna help you, you musta got knocked around in the ring too much in your boxing days when you was a chicken weight." "Bantam," Wallace replies. "I was a bantam weight."

- Johnson to Russell on the altering political landscape: "You know what the old soldier said when he was on parade? 'Hey, look! Everybody's out of step but me.'"

Third is Rauch's direction. Christopher Acebo's set resembles a legislative arena surrounding a space that, with changing props, serves as the Oval Office, King's kitchen, Johnson's bedroom, or a hotel room. The backdrop is a screen on which is projected settings, TV news footage, and a countdown to Election Day. Actors awaiting their characters' next appearances occupy the outer seats, watching the White House and the civil rights meetings acted out in the center, and either they move into the arena on cue or stay where they are to talk on the phone with Johnson. The dialogue is quick-paced, Johnson moving from one phone call or meeting to the next in breakneck speed while Deborah M. Dryden's lighting keeps pace. Actors briskly transition from character to character. As he did with his direction of Equivocation in 2009, Rauch keeps his actors almost constantly on the move—giving them pause only for the most key introspective moments—and segues scenes so quickly the production effectively crunches clock and calendar so that in three hours' time we feel we've lived a full year, one that passed by super fast. Rauch's direction makes even the most conversational of plays action-packed theater.

Lady Bird Johnson (Terri McMahon) and the president (Jack Willis). Photo by Jenny Graham, Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

The fourth aspect of perfection is the acting. It's not fair to single out any specific actor because all are in top form; this is as solid an ensemble performance as you will ever see. Still, we must mention the two leads who achieve the impossible—making us see them as the original historic icons they were portraying rather than imposing our own image of those iconic figures on the presenters. Jack Willis not only nails Johnson's Texas Hill Country dialect, he captures what came to be known as the "Johnson Treatment," the president's way of talking that comes across as down-home friendliness and ego-stroking supportive but carries strains of cajoling and threats. Humphrey (Peter Frechette) sums up the Johnson Treatment this way: "The question is, did I hear him say what I thought I heard him say? Or did I hear him say what he knows I want to hear him say?" His personality had more cache than his fame. Kenajuan Bentley fleshes out King to give us the man beyond the pulpit. King was one of the greatest public speakers of all time, but the private King was not so self-assured as he worked hard to organize a movement and build consensus, constantly molding the divergent goals and personalities of the various civil rights organizations into his overriding agenda. His fame had more cache than his personality.

He and Johnson share three key scenes in All the Way, but they are each always on each other's minds, antagonists against each other though fighting for the same thing. We also see the two heroes' tragic flaws emerge: Johnson's need to be liked and his obsessive drive to control even things far beyond his reach; King's need to maintain his status as the nation's preeminent black man and his desire to appear ever holy despite being merely human. Still, over the course of the play, both men seem invincible, giants with the moral courage and physical will to effect social change against all odds. But the play's ending (and our own knowledge of subsequent history) foreshadows how the attributes that made them such great leaders and politicians turn out to be the very qualities that would lead to their downfalls. As Johnson promises the audience that someday soon "they will gut me like a deer," we already see King's gutting begin off to the side, and Wallace is smirking: "Ain't nothin' over," the defeated Alabama governor says. "It's just gettin' started."

Eric Minton

August 19, 2012

On Broadway

Oregon Shakespeare Festival and American Repertory Theater, Neil Simon Theatre, New York, N.Y.

Saturday, March 29, 2014, R–111&112 (rear stalls)

Directed by Bill Rauch

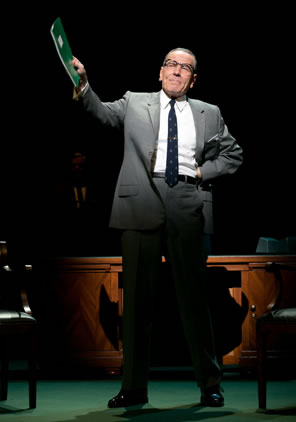

On its way to Broadway via a sold-out run at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., the Oregon Shakespeare Festival's Bill Rauch–helmed production of Robert Schenkkan's All the Way picked up a special ingredient: Bryan Cranston as Lyndon Johnson.

Bryan Cranston as Lyndon Johnson in All the Way. Photo by Evgenia Eliseeva, Jeffrey Richards Associates

His involvement is unquestionably the reason the play sold out in Cambridge before previews even began, and it factors in to the show becoming OSF's first-ever Broadway presence and a hot ticket, to boot. There's no question that the bulk of the audience at the Neil Simon Theatre were there to see Breaking Bad's Walter White.

The Emmy Award–winning Cranston is unquestionably a good actor, and his skills at physical transformation are on full display here. Too much so, perhaps. He plays Johnson as a caricature of a Texas politician inspired by caricatures of LBJ. He's an aw-shucks old man, constantly hoisting his pants at the waist and mugging both to his colleagues and his audience. It's funny; it's just not Johnson, the virile politician who used incisive humor and a mastery of negotiating skills to navigate impossible political dilemmas that would suck most other politicians (and every other politician in this play, including Martin Luther King Jr.) down like quicksand—in other words, exactly the sharp portrayal of Johnson we saw originated by Jack Willis in the OSF version.

Either over-the-top or two-dimensional portrayals are the hallmark of this Broadway cast. I'm not sure if it's the actors who know they are an orchestra of second fiddles to Walter White or whether Rauch has decided to resort to caricatures as the only way to get the play's relevance across to Broadway audiences out to see a show instead of being taught American historical drama. For example, understudy Danny Johnson plays King as if every line were a sermon from the mountaintop, even if it is just to say, "Go ahead! I'll be there in a minute." That's the King we see in newsreel retrospectives, not the King, as authentically portrayed by Kenajuan Bentley at OSF, juggling personal demons, financial demands, and political reality with his public persona as Civil Rights messiah.

Exceptions to the castwide tendency to un-subtle their portrayals are William Jackson Harper as Stokely Carmichael and Eric Lenox Abrams as Bob Moses, both of whom give earnest impatience and intellectual power to these two largely forgotten Civil Rights Movement heroes. J. Bernard Calloway, meanwhile, portrays the Rev. Ralph Abernathy with a dignity wrapped in human kindness as he assists Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in his mission. A humorous moment I don't recall from the initial production (and not in the script, either) comes when King has mediated an argument between the young studs of the voting rights movement and NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins (Peter Jay Fernandez). After the warring factions depart, Abernathy jokes about how much Wilkins and Moses dislike each other, a commentary that not only gets King laughing but also cracks up the two FBI agents listening in on their tape recorder. It's an interesting perspective; how much did the agents come to feel themselves part of King's inner circle as they eavesdropped on his every move?

This is the very human aspect of the historic events of 1964, events that will yet directly influence the coming national elections of 2014. It's perhaps a reflection of our own times that the production now portrays these players as types rather than real people and the methods by which Johnson brought landmark legislation to pass as broad humor instead of the hubris of true leadership.

Eric Minton

April 3, 2014

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances