King Lear

Olivier vs. Lear; Young vs. Old

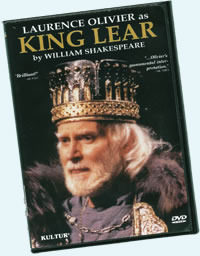

Granada Television (1984), Kultur Video

Directed by Michael Elliott. With Laurence Olivier (King Lear), Dina Rigg (Regan), John Hurt (Fool), Colin Blakely (Kent), Dorothy Tutin (Goneril).

This is an old King Lear, in every sense of the word. Though filmed less than 30 years ago, it has a soap opera-like production quality with mostly stationary acting—it's BBC Shakespeare done slightly better—and a penchant for dramatic bludgeoning (an intrusively heavy-handed score, a night-time battle, the armored Edgar appearing in a blinding backlight like Superman standing astride earth). It's also an old Lear played by an old Laurence Olivier, then 76 (being in your mid-70s in the '80s is the same as being in your mid-80s today).

This is an old King Lear, in every sense of the word. Though filmed less than 30 years ago, it has a soap opera-like production quality with mostly stationary acting—it's BBC Shakespeare done slightly better—and a penchant for dramatic bludgeoning (an intrusively heavy-handed score, a night-time battle, the armored Edgar appearing in a blinding backlight like Superman standing astride earth). It's also an old Lear played by an old Laurence Olivier, then 76 (being in your mid-70s in the '80s is the same as being in your mid-80s today).

That, however, is one of this production's chief qualities and most valuable contribution to a fuller appreciation of this play: age is a key thematic arc, and being old is King Lear's primary tragic force.

This was the second time Olivier played Lear. He was 39 when he first starred in a production he directed for the Old Vic, and he notes in his memoir, On Acting (Simon & Schuster, 1986), that "when you've the strength for it, you're too young; when you've the age, you're too old. It's a bugger, isn't it? The Romeo syndrome in reverse." The young-actor Lear can rant and rage his way to madness; the old-actor Lear understands that anger affects seniors differently. "The austere command of years can be conveyed just as powerfully, perhaps even more so, if played with steely calm," Olivier wrote.

That factors into his portrayal of Lear in this made-for-television production, but he doesn't pull it off altogether convincingly. He delivers the heath speech as just that, a speech rather than an outburst of rage or a display of a mental state cracking. It plays more like Olivier making sure he gives a darn good speech, for despite Olivier's career-long reputation for completely and convincingly transforming his physical self for a stage role, Olivier's ego never undertook such a full transformation. Olivier being Olivier will crown any role, and thus Lear the character seems to vie with Olivier the actor for screen time, rolling his r's in the grrrrrand tradition of the great trrrrrragedian. "Oh, rrrrreason not the need!" he proclaims (not wails, not whines, not seethes, but proclaims) as Olivier sticks his landing on the play's crux line. Sure, that's the actor showing off, but it's still a thrill watching Olivier showing off.

But just as the actor emerges at the grrrrrandest moments in King Lear, it is also difficult to discern aging actor from aged character in the exposition portions of the play. Is it Lear or Olivier who seems disinterested in the proceedings? I'll tilt the zebra stripes argument to the actor by noting that he nails the mad scenes; the actor seems less distracted when the character is most distracted. Thus giving him this benefit of a doubt, such a disinterested Lear is Olivier at his most brilliant; and if it is Olivier who is faltering, it's still perfect for the role. However, Olivier himself may not have been able to discern part from player, either. "Lear is an easy part, one of the easiest parts in Shakespeare apart from Coriolanus," he wrote in his memoir two years on from this second performance. "He's like all of us really: he's just a stupid old fart."

As portrayed by Olivier, Lear is a man desiring to ease into a life of retirement while maintaining his stature and dignity. He's impatient, he's totally self-centric (and thus bored with anything not having to do with himself), and he's short-tempered, all natural tendencies in men who know their days of living are reducing exponentially. Olivier's Lear also shows lapses of cognition in conversation. His arrival at Gloucester's manor is most effective in this, his mind darting from subject to subject based on visual cues: anger at seeing Kent in the stocks, even angrier seeing Gloucester without the Cornwalls in tow, suddenly shifting to sympathy thinking Cornwall may really be sick (the first time in the play Lear shows empathy of any sort), back to anger again seeing Kent in the stocks, soothed seeing Regan, angry seeing Goneril, relief seeing Kent out of the stocks, angry seeing the sisters exchange greetings, and devolving into confusion as his daughters verbally whittle away at his "needs." This Lear knows his body and mind are frail. This above all else bothers him because not only can he no longer do what he did in his youth, he knows that he's in an irreversible decline, and the retirement he had longed for is being withheld from him.

King Lear is most often seen as a tragedy of metaphysical implications, raw human nature vs. universal order. Director Michael Elliott plays to this in his setting the court scenes in a Stonehenge-like temple and modeling the landscape on the barren moors of western and northern England. The trappings of civilization are nowhere in view, and every shot is dark and foggy. Tanya Moiseiwitsch costumes the court in Arthurian-type robes and dresses, and the battle gear resembles that of ancient Sparta.

But the actors play to a different conflict: old vs. young. I've never noticed before how much this theme resounds throughout the play, from Kent (Colin Blakely) stabbing Lear to the heart with his retort, "What wilt thou do, old man?" to Regan plucking Gloucester's beard "so white, and such a traitor!” Edmund (Robert Lindsay) builds his conspiracy on the false evidence that Edgar (David Threlfall) believes their elders should step aside and let the younger generation take control, and we see this belief played out by the Cornwalls; the manners espoused by Gloucester (Leo McKern) and the courtesies demanded by Kent disguised as Caius—protocols of the older generation—annoy the Cornwalls past patience. The most heartfelt line Olivier delivers in the entire play comes when Lear tells Cordelia, "I am old and foolish." The play ends with Edgar stressing the tragic fate of aging: "The oldest have borne most."

The specter of aging plays out in duality in the portrayals of Lear's three daughters. Goneril is the oldest of the daughters who not only has had the longest exposure to her tyrannical father but grew up under a Lear that was younger and more virile than the Lear her sisters knew as children. Plus, she probably suffered the fate of being the eldest with all the emotional baggage that goes with that. Dorothy Tutin keeps Goneril ramrod stiff, reserved and incapable of real love; it is longing rather than real passion she feels for the strapping Edmund. When she admits to poisoning Regan, she doesn't necessarily say the line as an aside—Regan even seems to hear it and understand the implications. Goneril is, it turns out, every inch a Lear.

Diana Rigg plays middle child Regan as an intelligent schemer. The nature of her personality is succinctly summed up within her first few lines, proclaiming her love for her father. "Sir, I am made of the self-same mettle that my sister is, and prize me at her worth," she starts. "In my true heart I find she names my very deed of love—" and here, after seeming to establish an alliance with her elder sister, Rigg shoots a sideways glance at her: "Only she came short." Rigg continues with a knowing gleam in her eye and the sweetest of smiles (Goneril is incapable of smiling, of which Regan is all too aware), and Olivier's Lear relishes this competition between his two daughters. That smile comes back to haunt Lear, though. When he later complains that "I gave you all," Rigg uses the same smile, but the knowing gleam now has an edge: "And in good time you gave it," she says with a steely sweetness. Rigg's Regan gets in the heads of every man she encounters, filling them with dread and desire in equal measure, unnerving them all, including Edmund. He may tell us he's not sure which sister he would end up with, but Regan has already made it clear from the instant she meets him that she will have her way with him. When Cornwall is wounded by the servant during the Gloucester eye-gouging scene and calls on Regan to "Give me your arm," Rigg merely stares back, killing him with her apathy. Olivier's Lear may be the headliner of this production, but Rigg's Regan is its standout performance.

Anna Calder-Marshall is Cordelia, the youngest daughter, Lear's favorite. You have the father/baby girl syndrome going on there (they enter the opening scene walking with their arms around each other, giggling over some joke), but you also have a daughter who is relatively naive to the tyranny her sisters longer had to survive, thanks to her being younger and Lear being older. The opening scene is staged with much not-so-subtle blocking. The court lies prostrate before Lear as he takes the throne, and he makes a point of forcing both Goneril and Regan to do so again before they begin their love spiels. Cordelia, though, answers without even a bow. When Lear fully understands what his little girl is saying (and maybe realizing for the first time she's no longer his little girl but about to become a duchess or queen), Olivier casts her a weak smile and an importuning look as if to say, "Cordelia, come on, play along. Please."

Another relationship full of subtle dynamics is that established between Gloucester and Edmund in the opening conversation with Kent. Gloucester is so saucy talking about Edmund's conception that Blakely's Kent seems embarrassed for the bastard son. Edmund patiently stands by, and just as patiently stands by to hear the news that, though he's been abroad for seven years, he's being sent abroad again—patient, but bothered, too. This may set Edmund's villainy in motion, but the relish with which Lindsay's Edmund carries it out derives from his growing impatience with his father's foolishness and age.

In playing the Fool, John Hurt takes to heart the report that with Cordelia's banishment "the fool hath much pined away." Hurt's Fool is still pining, and pines with every line, every joke, every song. It's almost too pathetic. Still, seeing him abandoned in the hovel, shivering beyond control in the cold while the king and Kent depart for Dover—forgetting to take the Fool with them—is a barometer of the play's tragic impact.

Another interpolation undermines a later tragic moment. We get a sequence of scenes showing the mad Lear trapping a rabbit and gutting it (not for squeamish animal lovers) and then fashioning his coronet of weeds. These are spliced in between the blind Gloucester's non-fall off the cliffs of Dover when Edgar has rejuvenated his spirit and his meeting the mad Lear. Shakespeare brings Lear on right at the moment of Gloucester's self-redemption to such devastating effect, not only for Gloucester but for the audience, too. The intrusion of the other scenes—not to mention us still thinking about that poor rabbit—neutralizes the impact of this moment when Gloucester learns the king he adores so much has slipped into total senility.

For the famous entrance of Lear carrying Cordelia, Olivier moans out the first three "howls" distinctively but his fourth howl is a multiscale cracking heart. However, this is not a grieving or bewildered Lear mourning his dead Cordelia; it is a frustrated Lear, frustrated that she won't breathe, frustrated that everybody else who matters less are alive and she's not, frustrated that his wits seem to be leaving him again, frustrated that while he killed the captain hanging Cordelia, he couldn't save her, and frustrated that in his younger days he would have been able to do both. "I have seen the day with my good biting falchion I would have made them skip," he says. "I am old now, and these same crosses spoil me."

This particular ending had a strange effect on me. In most productions I've seen on stage and every time I read the play, I inevitably cry at the end. Olivier didn't make me cry. He made me worry. I'm getting old, too.

Eric Minton

October 19, 2012

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances