Sarah Smith stands in the Folger Library's Great Hall before a play in the Folger Theatre. Ever present hanging from her shouldeer is her "brain," a purse with her phone, a notebook, and other matter to supplement her limited memory capacity. Photo by Eric Minton.

The Tide of Truth

Sarah's Chronicles

The truth really started about four years ago, in 2016. Maybe earlier, because for a couple years before that, my wife, Sarah, began taking me for granted in noticeable ways. She would repeat news I had just told her minutes before, ignore my requests, take no notice of little treasures I'd leave around the house, and often seemed to be somewhere else when we were together.

Was she under too much stress in her job? A retired Air Force colonel, she was working as a consulting researcher for a firm contracted to the Department of Defense.

Was she slipping into early onset demenia? Her mother had Alzheimer's, which became noticeable in her 50s.

Was she having an affair? She was recalling shared moments with me that I knew weren't actually with me. I even began jokingly referring to this mystery person as "Brisket Man" based on one of those memories. If she were happy with him, great; just let me have the recipe.

In 2016, what I had considered annoying episodes of disregard became more alarming in their nature and frequency. This was the year after Sarah's heart (the anatomical one) began malfunctioning and then, unrelated, she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. By the middle of 2016, this immensely intelligent woman of great wherewithal, a 29-year, three-time-commander Air Force officer, wasn't able to track my instructions on posting an article to this website (a simple process she'd done countless times before) and couldn't grasp New York City's one-way street grid (we visited the city at least a half-dozen times every year). I was certain something was wrong. Either she had suffered a brain "injury or insult" (in medical terms) from one of her heart-stopped fainting spells of the previous year or from her radioactive treatment for the cancer. Or, she was indeed following her mother's path into dementia at a young age. Her doctors didn't see what I saw, testing proved her mentally fit, and she kept getting praise and bonuses at work. Was I wrong? Maybe Sarah was simply aging and I was overreacting, which seemed to be the doctors' collective opinion. All I could do was watch, worry, and try to adjust to my suddenly stupid wife—I have little tolerance for stupidity.

This chronicle, and the purpose of my posting it on Shakespeareances.com, traces to the Shakespeare Canon Project in 2018 when I set out to, and ultimately accomplished, seeing in one year every Shakespeare-penned play, each at a different theater across the North American continent. Sarah's seizures began hitting in March that year, and as that mysterious ailment worsened, so did her cognitive issues. All of that I included in my Canon Project chronicle as it threatened to waylay the endeavor. Loyal readers and the theater people Sarah and I encountered during that year began sharing their concern and prayers and taking inspiration in our determination. I continued posting updates on Sarah in 2019 as her seizures were finally diagnosed as epilepsy (and appropriately medicated), and, subsequently, she was confirmed to have dementia. The link to those essays, the prequels to this history, are

The Worst is Never the Worst until the Worst: Finding Comfort in Edgar in Times of Woes

Time's Passages: My Love's Labor Now My Winter's Tale

The Comeback: A Tragedy Overtakes a Blissful Comedy

The Tragicomedy of Errors: A Passion Play

Sarah had become a hero in the Shakespeareances.com community, and my accounts, always grounded in some Shakespearean allegorical strand, were appreciated as life lessons. One response to my most recent posting on Sarah, "The Tragicomedy of Errors," came from Christina Lang, a nurse Sarah and I met on our Shakespeare Canon Project travels, who called my essays on Sarah's medical journey "a beautiful script in the process." She described "The way you portray your love and concern for your wife's condition and progress with all the human feelings of fear, exhaustion, anger, and selfishness. Not to say you are a selfish person, it is only human to feel dragged down or put upon in this situation, even though you would do anything for Sarah. Watching the play that is Eric & Sarah is as captivating and enthralling as any Shakespeare play ever written."

She compared me to Shakespeare! Oh my! More importantly, she points out a key ingredient to all of my essays, reviews, and commentary: my honest self-portrayal, which is essential in discussing Shakespeare's acute insights into human nature. Dementia is human nature in one of its most tragic forms, and my way of coping is to write about it with brutal honesty.

"Sarah's Chronicles" will be an ongoing account of some of our journeys' benchmark moments, a front-row view into humanity's duality of strength and frailty. Shakespeareances.com is intended to express Shakespeare's daily relevance in and commentary on our 21st century lives, and I think it's apt to use this website to stage the Shakespearean tragedy Sarah and I are living in real time. I admit I have a selfish intent, as well: Often I feel a dire need to vent, and I can do that here where my audience can choose to listen or not without feeling cornered.

Sarah has read all of my articles for Shakespeareances.com before I post them, including those about her medical issues. She has given her approval to this project, though in time she may not read every entry before posting. Accounting for her memory lapses, I've asked her permission twice, three days apart. The second time she replied "yes" with even more firmness than her first time. Sarah is ever a woman committed to public service and enlightenment.

A friend said to me a few months ago, "She's lucky to have you." "I'm lucky to have her," I replied with the instancy of truth. That she is still my wife continues to be the greatest blessing of my life, and I'm proud to profile this woman of great courage and, still, mighty intelligence.

Wednesday, February 19, 2020—Stumped

"She started asking me stupid questions," one of my colleagues at the Commission complained, describing a doctor's appointment he'd had that morning. Questions like what day is it, what year, who is the president, who was the president before the current president. Finally, he said, he got fed up and told the doctor, "This is stupid. I'm leaving."

"She was doing a dementia test," I told him. "Sarah gets those all the time."

"But I don't have dementia," my friend said. The doctor still doesn't know that, I didn't reply.

Sarah got another such test today with her neurologist, Dr. Ruben Cintron in McClean, Virginia. He was the first of what are now three neurologists tending to her. Sarah became his patient when she started having those mysterious fainting spells in the winter of 2014, which turned out to be a cardiopulmonary issue: her heart would inexplicably stop for a few seconds. Dr. Cintron continued to see her every six months due to my concerns about her ongoing cognitive issues. When Sarah began having seizures in March 2018, Dr. Cintron moved to the vanguard among her tending physicians. Unable to determine the cause of her seizures or their connection to her by-then-obvious cognitive disability, he managed her referral to Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, where Sarah was assigned to a second neurologist. Tests diagnosed Sarah's epilepsy, and treatment for that has been successful. However, the tests determined that the seizures had nothing do with her diminishing cognitive capabilities. That led to a round of psychiatric exams which led to her now being treated by a Johns Hopkins neurologist who specializes in dementia.

We still see Dr. Cintron every four months for checkups and counsel. And, he always puts her through a rudimentary dementia test with questions that measure her awareness, tracking abilities, and short-, mid-, and long-term memory.

He asks her the day. "Wednesday," she says.

He asks her the month. "Um, February."

He asks her the date. "19th?"

He asks her the year. Takes her a while, but she finally gets 2020.

He asks her to spell world. "W-o-r-l-d."

He asks her to spell world backward. "D-l-r-o-w." I exhale in relief: that's a hard one for me.

He asks her who is the president. "Trump."

He asks her who is the vice president. "Pence."

He asks her who is the Secretary of State. "Pompeo."

He asks her who is the Attorney General. "Um, oh, Barr."

He asks her the date of our wedding anniversary. Her vocal sound effects are evidence that she's thinking. She finally narrows her answer to late June.

He asks her how long we have been married. More groans and moans indicate the mind's memory cogs are at least moving. During these tests, I remain silent and expressionless. I offer no hints or, in this case, no snide comments about how she and not me doesn't remember our anniversary date. She gives up.

Dr. Cintron asks her, "Who is your husband's favorite writer?"

She is lost in either a maze of many potential answers or an absolute abyss. She doesn't even hazard to guess. For more than a minute she ponders, physically trying to catch the answer as she shifts in her chair, me sitting by with no expression whatsoever. Dr. Cintron patiently waits before moving directly into wrapping up the visit with his summary instructions for follow-up.

As we leave Dr. Cintron's office, I ask Sarah if she still can't remember my favorite writer. She has no idea.

"I should put this on Shakespeareances.com," I tell her. She doesn't get the connection.

Saturday, March 14, 2020—The Menu

The window to our world from my home office. Photo by Eric Minton.

The coronavirus has officially turned into a home-growing pandemic. I'm spending the weekend monitoring postponed shows, cancellations, and theaters closing across the continent so that I can report these developments on Shakespeareances.com and update my Bard on the Boards lists, which already are woefully behind. Today, I'm devoted, I'm energetic, I'm doing concentrated work—a rarity for me of late.

Sarah sits at her desk adjacent to mine in my home office. She's surfing news sites, rereading the same stories. I sense she's bored and don't want to be negligent, so I ask her, "Do you want to help me out with something?" She jumps at the chance.

For her to "help me," I have to come up with a task she can do without my help: helping her helping me kind of negates the purpose. I've got just the thing, a real need, though not urgent. We've been reworking our Shakespearecurean meals as we work toward publishing recipes that we began developing 30 years ago. We have finalized six plays' worth of three-course dinners and buffet-type brunches along with a themed soup and themed salad for each play. With all the recipes in separate computer files, we need a formal menu listing all the dishes by play.

Sounds menial, but I presume she can't handle anything more complicated. I transfer the recipe files to her computer, set up a master menu document, open the first set of recipes, and show her what to do. I leave her alone and get back to my work.

After 45 minutes, I look over and see her reading the first menu. "How's it going?" I ask. She tells me she has just finished editing the menu and made some changes. Well, these recipes had been finalized and edited months ago, but OK; she's at least engaged, and I will transfer her new version into my files. I look at the menu document. There's nothing on it.

Sarah forgot that was her task. So, guiding her through the process, I list the first dinner's dishes on the master menu. "Do you think you can do that?" I ask. She says she got hung up on how to describe the dishes. She has a vast menu collection, so I get one from her collection, set it on her desk as an example, and pull up the next dinner on the computer for her. She affirms she can do the rest, but she sounds tentative.

Time for some tough love—gently, of course. I reiterate that if she can't do it, we don't do it, because I can't spend the day helping her help me when I've got more urgent work to do. I'm unequivocal on this point, but I speak in a gentle, nonjudgmental voice. She understands, takes a breath, readies to work—and stares at the screen as her fingers remain motionless on the keyboard. I place my hands on her shoulders and kiss her scalp. "If you don't think you can do it," I tell her softly, "Then say so. It's OK."

"I don't think I can do it," she says. Her honesty is actually a breakthrough, but her tone of resignation breaks my heart. Nevertheless, I stay light. "I'll get to it before too long," I say and sit back down at my desk.

Sarah goes back to surfing news pages, the entire episode already dissipating from her memory. My mind is not so kind to me. What I just witnessed constitutes a new level of cognitive incompetence, another benchmark in her unrelenting slide into dementia. Still, what was I thinking? Why can't I adjust to this new reality?

It's frustrating having to constantly adjust to my evolving comprehension of how her mind is working and forgetting that she is operating on a different level of logic (or illogic) than I am. For example, because Sarah has no spatial understanding, I have to give her specific directions to pick up something in plain view on a countertop. I ask her to get me the balsamic vinegar among our cooking spirits and condiments, which are lined up in a trough on our prep counter. I tell her they are arranged alphabetically. Great, Eric! even if she could still work out the alphabet, she wouldn't know in which direction to move her searching hands.

I have learned to give her instructions one step at a time. The script goes like this: "I need a measuring cup. Go to the corner cabinet." She does. "Look on the second shelf." She does. "I need a half cup." She takes down a one-cup measuring cup. What she actually does I can never anticipate, so it becomes more improv.

"Go to the corner cabinet. No, the other corner. Right. No, up—the cabinet above the counter. No, to the right of that one. To the right. That's left. There," I say, by now leaning over the kitchen peninsula to point at the target cabinet, which I could have easily opened and gotten the damn measuring cup myself. She opens that cabinet door, and I confirm this small victory with, "You got it. Second shelf. No, second shelf. No, the one above that. The SHELF above that. The—right, now, no, a measuring cup, a fluid measuring cup. No, the one to the left. The left, right next to your hand. The other way. No, left of your—YES, that one!"

I strive to contain my frustration, but it's hard. Any frustration she experiences passes in a minute. For me, they linger for a lifetime. I kind of envy her, but I don't dare cast myself as the victim. The real injustice has been imparted to her. But she keeps trying. "Thank you, my love," is the only right thing to say.

Saturday, March 21, 2020—The Tip

This day starts off great.

I drop Sarah off at Jon David Salon where she gets her hair cut and colored and spends time in the company of her friendly hair stylist, David Bakir, and his attentive staff. I go on to our supermarket to shop for the weekend's Shakespearecurean cooking, take the food home, visit with our neighbor (keeping some 12 feet apart), and then Sarah calls. She is finished at the salon, but she has a question: which credit card should she use? I tell her.

What strikes me wasn't the question but the tone: she sounds frustrated. With me? "Are you ready for me to pick you up?" I ask. She says she is. A tinge of curtness edges her voice.

I remember she didn't have any cash to use for tips. That happened at her previous appointment back in December, and I still regret that. So despite the annoyance I hear in Sarah's voice, I detour to an ATM to get tip money. I reach the salon, park, and as I walk down the sidewalk, she heads my way as pleased as a kid at Christmas. I make much over how good she looks, which is totally honest: she no longer looks like a skunk with a gray stripe at the roots where her hair parted (yep, I say that out loud: she laughs). I give her the tip money. "Oh, I needed that," she says, and gleefully goes back into the salon to dispense it.

These are the moments I live for now, when she becomes an embodiment of pure joy, even over such simple pleasures and right outcomes. In spite of everything she's been going through, Sarah's grace and exuberance has never abated, a woman with the style of a cool cat and the demeanor of a puppy dog.

When we get home, I check my emails. There's one warning that one of her credit cards had been used at an ATM and was shut down because of too many incorrect passwords. The scenario plays out in my mind explaining the chord of disharmony in her voice when she called me: She needed cash, the salon has a cash machine, she used her go-to card, made various password attempts, was locked out, and called me to find out which card she should use to pay the bill. With the email evidence in hand, I ask her to verify if my scenario was correct, and she confirms.

Her inability to remember passwords paired with her stubborn attempts to log on to various accounts until she gets locked out has been epidemic in its occurrence, causing me exponential trouble and time to right things. I can't get her to change this habit, and once again, here I am lecturing about her need to accept her condition and be smart. My tone is kindly, yes, but still: "be smart"? Yep, I still say that, and still expect it, too. It occurs to me—as it always does too late—that the loving voice I use is irrelevant. Her good day has been sidelined as I see her happy demeanor fade into the understanding that she's causing me more trouble. And with that shift in her expression, my good day is sidelined, too.

Why can't I just let these episodes pass without comment? She will not change. She can not change. She's not going to suddenly learn the lesson. She's struggling. I struggle to alleviate her struggles and end up reminding her of her struggles while hammering her about my own struggles with her. It's a vicious cycle I could stop simply by swallowing the consequences for me and concentrate on turning the experience into a lesson for me on how to handle similar situations better in the future.

This resolve is tested within minutes. I empty the dryer and discover another lapse. "You didn't hang-dry this shirt, and the stain is baked in," I tell her. Kindly, of course.

Tuesday, March 24, 2020—Done Driving

Sarah's driving days are past. With her second seizure in spring of 2018, she, by state law, would not be able to drive until she had been seizure-free for at least six months. The same rule applied when she had her heart-stopping moments in 2014–2015. Six months after that condition was solved with a pacemaker, we were driving to visit my dad in Charlotte, North Carolina. I pulled off the highway and said, "Do you want to drive?" I'm not sure who was more ecstatic at that moment: Sarah, who finally got to enjoy a new car she had only driven a couple of weeks before the fainting spells took hold, or I, who had grown weary of driving everywhere, every time.

This time, 14 months passed before her seizures were brought under control with medication. Then, before six additional months passed—before the day I had marked in my calendar, "Sarah can drive"—her dementia was firmly diagnosed. She will never drive again. Probably time to sell one of our two cars, but I keep resisting.

However, when our AAA annual membership came time to renew, I figured there was no reason to pay for her to be on the account. Indeed, she was the actual member, and I was an add-on family member. Per instructions I received from AAA, she had to call in order to make me the primary member and remove her from the roles. I dial the phone and put the speaker on. "Ernest" answers, and Sarah gives this opening explanation: "I have a seizure disorder and nobody wants me to drive anymore."

I don't know if she said that as, A), cover, not wanting to say she has dementia, as the seizures are under control, or, B), that is what she really believes, perhaps unaware she has dementia. I so want to learn that truth, but I decide not to ask. An answer would likely disappoint, and it makes no difference, anyway.

I inadvertently walk into the answer later. I wrote this and the first three entries before I made the decision to post this chronicle on Shakespeareances.com. In asking Sarah for her permission, I read through the entries for her. She listens to this one and says, "I can tell you why I said that. Do you want me to?" I really don't, but I hem and haw long enough for her to give her reason: One of her cousins has a friend in Maryland who continues to drive, she says.

"What is her condition? What does she have?" I ask.

"A seizure disorder. But they let her drive, and nobody allows me to."

I shouldn't have hemmed and hawed.

Saturday, March 28, 2020—The Dishwasher

I never realized how narrow-minded ego could be—an egotistical ego, if you will—until I became my father's caretaker. It wasn't my dad's ego I encountered, as demanding as he could be in his post-stroke struggles to regain the humanity he had been so used to. It was my ego.

Umpteen times I took him to his various medical appointments, and he always gave me street directions. "I know where I'm going," I'd say. Or sneer. Or harrumph. Or sometimes seethe. Finally, I decided to head him off. A half-block from the next turn, I announced that I'll be turning right. Dad would still tell me to "turn right here." Perhaps he hadn't heard me, the stroke having enhanced his already substantial hearing loss. No problem: next time I shouted my intentions. Or yelled. Or bellowed. Or hallooooo'd. Still, he would tell me to turn right here. One time, he forgot to tell me to turn right here as the turn approached—or so I thought. "Where are you going?" he asked as I made the turn. I patiently told him we were going to doctor whomever today. He didn't reply, so it wasn't until I was nearing another doctor's office that I realized I had mixed up my directions.

Dad's stroke did not affect his intelligence, just his capability to express that intelligence and get specific parts of his body to carry out its commands. I always pointed this out to doctors, nurses, bankers, state and municipal officials, and customer service reps. I just hadn't pointed it out to myself. When I finally did, my ego found peace. After I'd get him in the car, I'd remind him where we were going, and as always, he started giving directions on how to get out of his retirement center's parking lot. How many thousands of times had I exited that parking lot?

But I merely said, "OK," and remained silent or engaged in small talk to the next turn. He told me where and how to turn. "Got it," I said, and made that turn. Approaching the next left, he told me to turn left.

"At the light?" I asked.

"Right, at the light," he said, then, in a panic, "LEFT at the light."

"Right, or, rather, left," I replied, a bit cheekily. He appreciated the humor, as I already was steering into the left turn lane.

I even got to the point where, a half-block from the turn, I'd ask if that was my turn. This was a bit more empowerment for him as well as assurance for me. Catering to his intent to always give directions ended up being liberating for me and not at all debilitating to my ego.

You'd think I would apply that lesson as caretaker for Sarah, whose motor skills are perfectly fine but whose intellect needs direction. I've gotten better at not reminding her how I'd just told her something by first reminding myself that with no memory of the moment she has no reason to be reminded. Yet, my ego still comes rising out of the murky depth like a wrong whale of bad intent.

Sarah has become creative in loading up the dish drainer as well as the dishwasher. Photo by Eric Minton.

As a freelance writer and editor who usually works at home, I managed the household while she commuted to work for most of our marriage and often deployed on military duty. I did the laundry, I did the cleaning, and I did the dishes (even on weekends, allowing her to savor unfettered time for reading the newspaper, one of her favorite pastimes). So, I have my way of doing laundry, cleaning, and loading the dishwasher. I know how to line up the plates to maximize space availability for the bowls and pots. I know what items are safer on the top rack. I know that you should always, always, place flatware and utensils in the rack one cubby hole at a time from front to back until every slot is taken and then repeat. One does not put them in the rack back to front, and certainly not two items per space at a time. Sarah would start from the back! She'd sometimes skip a space! She'd sometimes, OMG, put two in a space before filling out all the spaces! I'm the graphic designer in this marriage. I am "Son of Patsy," so-called by Sarah herself because my mother was a packer extraordinaire and my skills almost match my mom's in maximizing the use of space. These days, Sarah has been taking the lead in managing the dishwasher. It is a way she can contribute, so I've learned to give way to her desire, coaching her only when necessary but backing off when I notice perturbation in her demeanor. And, I admit, she did teach me the merits of placing wire colanders over bowls.

Today, though, as I need to clear the sink of dirty dishes before fixing dinner, and she hasn't yet joined me in the kitchen, I partially load the dishwasher. After dinner, she rearranges what I have done. Sarah rearranges how Son of Patsy had loaded the dishwasher. Is Sarah's rearrangement better? That's beside the point. I am hurt, and I say, "I know your condition can't help it, but it often seems you always only want to undo what I've done."

You want to read that again? Here, let me help you: "I know your condition can't help it, but it often seems you always only want to undo what I've done."

Sarah looks at me with baffled exasperation. I look at my ego with baffled exasperation. Ego slinks back into the murky depths of my self-conscience, dragging my pride down with it.

Saturday, April 4, 2020—Closing the Door

Heading into the second quarter of the year, I was reassessing my professional strategic plan and asked Sarah for her opinion. This is automatic for me: When I need wisdom, I turn to Sarah. Only after she starts responding do I remember that, these days, whatever wisdom she could impart will get jumbled up in her difficulty tracking the thoughts emanating from her wisdom.

This was one of those occasions, but in her answer emerged a new dimension of her condition: she started interweaving memories from two periods in her life into one memory. Only Sarah's short-term memory has been impacted by the dementia; here was evidence that her midterm memory might be wavering, too.

She was having a bad memory day: repeating herself (or me) two or three times, losing track of tasks, and frustratedly wondering "how that got there" when it was she who put it there. This bad memory day came after a day in which Sarah was her 2014 self, even landing a couple of sharp puns. This see-saw has become frustratingly typical: "good days" when I still get my hopes up followed by days with evidence of further deterioration. God at his cruelest.

Lately, Sarah has been closing our bedroom door when we go to bed. She didn't used to do that except when we have company. As I'm teleworking now but keeping my regular predawn work schedule, when I head downstairs in the morning I'll close the door so that my music and movement don't disturb her. I thought maybe this was confusing her, so I stopped closing the bedroom door in the morning but closed my office door instead. Tonight, she again closes the bedroom door.

"Leave the door open," I say, making sure I keep the exasperation out of my tone. My comfort level is to have the door open so I can hear any movement in the house, as well as the alarm system. But my curiosity is piqued. "Why have you started closing the door all the time?" I ask, even though I'm certain her answer won't stretch beyond "I don't know," or "I just do," or "I'm not thinking."

"That's what I've always done in the first-half of my life," she replies.

I'm flooded with a sense of "uh-oh," but I move right to humor. "But I wasn't in the first-half of your life," I say. "I'd like you to stay in this half." She laughs, I tease a bit more, and romance takes over, even as a new truth is washing over me. The times are a-changing—her memory's time.

Tuesday, April 7, 2020—Masked Man

My humor can be weird. I'll make word associations that swirl as non sequiturs into such silliness that I'm not even going to try to replicate the punchline to this story. These bizarre treks of humor, which Monty Python would reject as utter nonsense, have always made Sarah laugh. Shortly after we started dating, she told me she was getting crows' feet around her eyes from laughing so much. Laughter was something she said she seldom did before.

Today starts off with an uh-oh moment. I pour myself a glass of orange juice and Sarah a glass of apple juice. As I pick up my glass and start guzzling, she takes her apple juice into the dining room, comes back into the kitchen, and pours herself a glass of apple juice. She responds to my gaping look with assurance that the glass she's using is clean—it just came out of the dishwasher, she says. "But I just poured you a glass," I say. "Did you?" she says looking confused. Somewhat uncertain myself now, I look into the dining room, see the first glass of apple juice, and point it out to her. "Oh," she says, but before she can dwell on her lapsing memory, I tell her, "And now you have two glasses. Must be thirsty." I'm getting better at this.

Sarah's day turns remarkable, though, when she decides to make face masks for us. I will have to go into the Commission office the next two days, and, according to a policy the Department of Defense just issued, I must wear a mask on DoD property during the current COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Years ago, Sarah made curtains for our baseball room, featuring pinstripe fabric. These curtains had stars-and-stripes bunting tiebacks with plastic rings at their ends. Sarah remembers these, finds them among our stock of discarded fabric, and ties shoelaces to the rings, creating a simple but fully nose- and mouth-covering mask. I'll have the most patriotic face in the land. She does this all on her own: determines to make masks, figures out how to do them, finds the ingredients (amazing in our black hole of a house), and completes them, all while I am stuck in a series of teleconference meetings that last all day (sometimes I'd like to extend social distancing requirements to phones).

This evening, as we are doing dishes after dinner, my devolution of stupid humor begins innocently. I thought I heard her doing laundry today, so I ask what she washed. She doesn't remember washing anything. Trusting my hearing over her memory, I asked if she washed the masks, as those tiebacks had lain dormant in a wicker case for at least 25 years. I might not die of COVID-19, I tell her, but I might get the worst cast of fabric poisoning ever recorded. I'm just getting on a roll with the puns when I realize she's not laughing.

Turning to look at her, I see confusion in her expression. She's trying to understand my meaning, like, did she need to wash the fabric? Did she wash the fabric but forget to take the masks out of the laundry? I'm trying to read her mind, but what's clear is that she's trying to track my runaway train of thoughtless comedy and can't keep up with the non sequiturs.

"Never mind, it's fine," I bail.

OK, so I didn't exit from that one very well, but this is another adjustment in my behavior I'll have to make as yet another facet of her personality slips away from us. This may be one of my hardest adjustment of all.

Still, we were talking about the masks, so I dwell on that. She made those! That's the Sarah I've admired these 30 years, and I'm going to wear that Old Glory tomorrow with tremendous pride in my wife.

Sunday, April 12, 2020—Bunny Business

The Easter Bunny leaves a surprise for Sarah, as Santa Claus looks on in our still-Christmas-decorated library. Photo by Eric Minton.

Today is Easter, and our marriage experiences a first for this holiday.

Sarah and I are not big on holidays, except for Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Veterans (Remembrance) Day, which are the only holidays we pay special attention to. I've also always made a big deal over her birthday and Mother's Day with appreciative celebration of her existence in my life and my sons' lives. Otherwise, we approach holidays as a chance to do things together on a day off from work. Even days of singular observances, such as Valentine's Day and my birthday, generally pass with little more than token acknowledgement.

When I was a kid, my family did Easter baskets. We'd see them in the living room—but couldn't touch them—before we'd head out for the sunrise service. Sarah grew up with Easter baskets, too, and a couple of weeks ago, this came up in conversation; but in the present tense. She was expecting the Easter Bunny to visit us. Given that the Easter Bunny has never visited us, this was an example of her increasing tendency to blend long-past memories into her current state. I reminded her that we've never done Easter baskets together, and she paused, sorted out her memories, and said, "Oh, that's right."

The moment passed for her. But not for me. This morning, I direct Sarah to the library—still decorated for Christmas, as is the entire house because I haven't had time to take Christmas down, and Sarah won't dare do it without me. There, her Easter basket awaits her. It is the same basket that held the goods from her Christmas stocking, but as she had long ago tornadoed through all that chocolate, the Easter Bunny reused it, filling it with chocolate eggs, bunnies, bees, ladybugs, a chick, a squirrel (I don't know why), and pork rinds—Sarah loves flash-fried cholesterol. My basket from Christmas is still two-thirds full, so the Easter Bunny skipped mine, and I'm fine with that.

Sarah is in a good place this morning, sporting a supernova glow from some incredible romancing we did last night and this morning (I'm still mind-blown, too). She has remembered that it is Easter, and she's pleased with her basket, yet by her behavior I can tell she's still trying to comprehend why she received one. It didn't occur to me that she wouldn't remember our conversation of earlier in the week. I suggest that the basket will serve as a conduit for her quarterly chocolate fix: The Drummer Boy will fill it on Independence Day, and I'll take her out trick-or-treating for Halloween, which should last her to Santa's return. She laughs. She's content. Soon enough she's selecting a ladybug and a chocolate carrot for her initial assault on the basket.

No need to imagine what's going through her mind right now. For me it's another new memory from the never-ending generator of memories that is our relationship.

Sunday, April 19, 2020—Going to Church

Today is Sunday. The COVID-19 Pandemic is raging, and self-centered naysayers are raging dangerously loud. My anger boils over on Twitter. "Why, in the face of the pandemic's risk, are so many Christian ministers insisting on holding in-person services when Jesus CHRIST himself, in the lead-in to the Bible's most quoted verses (Matthew 6: 9-13), specifically and pointedly advocated for worshiping alone, in isolation?" I tweet. "The answer is obvious," I continue in my own reply. "I've long thought 'fundamentalist preachers' have never actually read the gospels. In this pandemic I've come to realize they have read them not to heed Jesus's teachings but to model themselves after the Priests and Pharisees who tried to silence Jesus."

My chief ministry right now is to make Sarah laugh. Indeed, it seems to me that Sarah has laughed harder and more often this year than in our decades together that we filled with great fun. Maybe this seems is of a relative nature, the laughter juxtaposed with my heartbreak. I'm sure that in my heightened humor I'm striving for my own solace, but my primary determination is to keep Sarah in a happy state. The problem is, I'm not preternaturally funny—except, perhaps, in unintended ways—and my wit runs at a turtle's pace. Rather, I rely on silliness. Sarah has dementia, but I have a demented streak in my personality.

Sarah's medication management center: weekly pill organizer, dishes with today's pills, index cards with the days of the week, and the pharmacy instructions. Photo by Eric Minton.

Sarah has a medicine regimen of seven pills for her heart disease, her missing thyroid, her blood pressure, and her epilepsy (notably, no pill for her dementia). On Sunday mornings we refill Sarah's weekly pill manager, a plastic box with seven columns and four rows of cubby holes. In these we place the pills she needs to take with breakfast, lunch, dinner, and at bedtime every day. This morning, I use our made bed to lay out the pill box, the pill bottles, and my accounting chart. I made that chart more than a year ago so that she can keep track of which pill goes where, but I've since taken over this weekly task because even the chart couldn't keep her straight. On her own initiative she has put four dishes on her dresser for that day's pills, a reminder tactic that has worked well for her; in my estimation it has cut down the incidents of forgotten pills by as much as 90 percent. Plus, it's easier for me to track her daily doses as I can glance at the dishes every time I pass by during the day.

I kneel next to my workspace on the bed, and that motion and location merges with the particular hour of this particular day. I enter the silly space.

As if intoning a Gregorian chant, I call upon the Levothyroxine Sodium and begin an impromptu homily on the merits of this pill. I have to put the first one in its today's dish on the dresser, so I remain on my knees as I cross the floor like a pilgrim moving toward a holy shrine, then back to the bed to place pills in the rest of the week's six spaces. Next up, Levetiracetam, "otherwise known as Keppraaaaaaa," I singsong, and repeat the pilgrimage. The singsong homily turns really ridiculous with the gummy multivitamin supplement, but now I have a rapt audience of one.

Realizing I can mine Catholicism only so much, I switch to Black Pentecostal mode, my sermon of the pills pinioned with Amens and Hallelujahs. I preach, Preacher! using my best Pastor Leroy cadence to press home the lessons of the Lord that we must abide by Ev'ry. Sing-le. Day. Of. The. Week. We're in the row of the lunch pills, now, which includes St. Joseph Baby Aspirin, and I call on the scriptures' recounting of Jesus and the children to drive home my lesson of love for Ev'ry. Sing-le. Day. Of. The. Week. "Can I have an amen!" Sarah looks at me, laughing. "I SAID, can I have an AMEN!" "Amen!" she says.

"Thank you and hallelujah!" I preach, and we're on to the dinner and bedtime rows, one pill for each. I go Lutheran, drolly naming the pills, referring to the bulletin (the chart) and the schedule of events for the coming week.

I often have heard it said that preachers' kids (PKs) are the most irreverent Christians. I certainly am. Furthermore, being an Air Force PK, I grew up witnessing and appreciating all of the above worship traditions. Every base had four or five Protestant chaplains and two Catholic priests, so the two Sunday services rotated among them over the course of the month. You want an aerobics workout? Attend a Catholic service. Chaplain Leroy was the only pentacostal minister my dad served with, and with its gospel music and sermonizing prayers, his shows, er, worship services were my favorite. My dad, by the way, was Southern Baptist with Anglican trimmings: a weird but wonderful combination.

I'm not making light of any of these faiths or their vital traditions, not at all—though I am making fun from them, because I'm just making Sarah laugh. Can I get an amen!

Monday, April 20, 2020—A Grinding Grief

Scrolling through the Internet yesterday, Sarah seemed upbeat but noticeably quiet as she re-read news stories at her desk behind me.

I was editing an article, due today, I had written for the magazine Professional Photographer, published by the Professional Photographers of America. The piece profiles William Castellana, a New York-based photographer who produced a children's book with his partner, set designer Linda Montanez. The book, Inquisitive Creatures, is a tale of three highly intelligent, juvenile foxes and a dog, students at a science academy, who decide to build a time machine. Montanez made the creatures out of felt, and she and Castellana built 1/16th-scale sets in a steampunk aesthete and incredible detail in the furnishings, including papers, books, and the inner workings of a clock. Castellana photographed these scenes using an illumination technique called light painting.

Such was the detail I had to describe in my article that I thought I'd get some backup brainpower. "You want to help me with this?" I asked Sarah. Of course she did.

I airdropped her a PDF of the book and asked her to familiarize herself with it. "Look closely at everything in the rooms," I told her. She can't do that in a real room, but maybe a picture on the computer would be different. After about 15 minutes of reading the book, she finally spoke. "I have a question," she said: "These are animals. But they're doing human things, going to school."

I didn't turn around, but said, "Yes?" with a tone that didn't quite mask my WTF concern.

"This is a children's book," she said: "Won't children be confused that these are animals doing all that?"

Now I turned around. She was truly confounded. "What about Bugs Bunny?" I asked. "Mickey Mouse? Disney's Robin Hood where all the characters were different animals?"

"I don't know about any of that," she said.

Dementia is a condition that crawls on to inevitability, but this is all happening too fast for me, and I can't stop the train. We all know how much pressure caretakers are under, but I never anticipated the endemic emotional toll. As her mental deterioration continues, I'm finally understanding the pain I'm feeling. It's grief. Not the shocking grief of loss but the grinding grief of impending loss. No amount of intellectual understanding can alleviate that gut feeling. It's not just that I know what's coming, but that some of what makes Sarah Sarah has died already, and with it the life I've grown accustomed to. Plus, the remainder of her is expiring at a faster rate than I anticipated, yet still slowly enough to maintain the flame of hope for a future that was like our blissful past. That's a tough double punch to the soul.

I've even begun envisioning the certainty of life without her, and that is contributing to my misery. It's a common conciliatory concept to believe that death after a prolonged terminal illness brings relief to the caretaker."She's in a better place, and so are you." But for us caretakers, death of our loved one comes well before the caretaking ends, and the grieving starts long before that. Nor will it necessarily end when her life ends. In fact, I can't imagine my grief will ever end. I will miss her sorely.

But not yet. Not quite yet.

Saturday, April 25, 2020—Crimini of the Heart

I give Sarah simple instructions: She needs a half pound of crimini mushrooms for her mushroom salad recipe. I leave her so that I can gather some get-them-quick-while-you-can-during-this-pandemic items: shortening, double cream, eggs. As I walk through the baking goods aisle on my way to dairy, a stocker is placing 5-pound bags of flour on the empty shelves. I hold out my arms and he hands off a sack as I pass by. Paydirt!

Arms full of goods, I hurry back to Sarah. She is just then putting two one-pound packages of bella mushrooms in the shopping cart. Um, Sarah, you need a half pound of crimini mushrooms. She says there were no criminis, so I ask her which she wants, baby bella or white mushrooms. She wants baby bellas, so I pointed to what I think are six-ounce packages, tell her to pick one, and I hurry off for a few more items. Heading back to the produce section, I encounter Sarah steering the cart into the supermarket's main central aisle with two one-pound packages of bella mushrooms in the cart. I gather up my patience, take her back to the mushrooms, and point, again, to the six-ounce packages. I leave her to get some produce across the way, come back, and she at last has a six-ounce package—well, she has two, in fact. Putting one back, I notice it's only five ounces, so I suggest a 10-ounce package, as that's just over the half pound called for in her recipe. She agrees and picks up a package of shitake mushrooms. No, the baby bella, I tell her. Right, she says, putting back the shitake and putting two one-pound packages of baby bellas in the cart.

Crimini Christmas! she's having a bad brain day. Really bad. I pick out a 10-ounce package myself and put it in the cart. Yes, she actually got it right when she had two five-ounce packages of baby bellas, and such exponential mental lapses between us happen a lot.

Nanna was one of 3,000-plus plush toy refugees from my parents' home after my mom (who collected them) died and my dad had a stroke. We took in several dozens, including Nanna, who now assists us in the kitchen and oversees Shakespearecurean recipes. Photo by Eric Minton.

This shopping trip heralds a significant shift in our long-term Shakespearecurean project. In the early flourishing stages of our courtship 30 years ago, Sarah and I began cooking menus inspired by Shakespeare's plays. Being the freewheeling, artistic cook, I built mine around the plays' themes, imagery, and characters. Being a cuisinologist with hundreds of cookbooks covering all eras and regions, Sarah created historical recipes attuned to the plays' settings. We shared our first several recipes with my father, who fancied them up on his computer and printed a cookbook that he shared with the rest of the family. My uncle shared his copy with a professional chef, prompting Sarah and I to stop sharing and start earnestly working on a publishable cookbook. We settled on a two-phase approach: My allegorical recipes would be Volume One, Sarah's historical efforts would be Volume Two.

The project spurted on and off over the years. My culinary skills improved, my insights into the plays deepened, and my menus broadened to include soups, salads, and omelets. Pairing wines became part of the adventure. My son suggested that what we called the "off meal" matinees (some lunches, some breakfasts) should be approached as full-scale brunches. Meanwhile, Sarah's historical cooking efforts tailed off.

About five years ago, we began a concerted effort to revisit and finalize our 30 existing menus and create the remainder. Then her dementia snuck up on us. I have come to accept that there will be no Volume Two, but I haven't quite accepted that Sarah probably won't be around intellectually to see the completion of Volume One.

Nevertheless, we can't drop her unique contribution to this passion, especially as some of our favorite Shakespearecurean recipes are Sarah's. I decided to merge some of her recipes into my dinner and brunch menus, including Insalate di Funghi Crudi (Raw Mushroom Salad) from her original Cymbeline breakfast menu. It is now a dish in our Cymbeline brunch. For the plays lacking her historical menus, we would work out her contributions together. That's not easy. I'm trying to get Sarah to describe how she approached the plays. She can't even identify cookbooks she used, once even picking out her father's Good Housekeeping cookbook: it's old but it doesn't feature Ancient Roman, medieval, or Elizabethan recipes. I start searching the shelves for any texts that might work for the menus we've otherwise finalized.

I come upon a cookbook with recipes for England's monarchs, including King James I's favorite chicken soup. Sarah never got around to doing a historical menu for Macbeth, and Shakespeare wrote that play specifically for James. However, my "Chicken Cawdor," a bloody chowder using pureed roasted red bell pepper as a base for the broth, is one of my faves and thematically perfect. True, James's chicken soup carries the "chicks" element of the play, and it uses eggs as a thickener, so there's the play's progeny theme. But the recipe looks hard and not appetizing.

This should be Sarah's decision. I lay out the pros of each soup. Without pause, she chooses James. I'm disappointed. With an I-know-Shakespeare superiority tone, I point out that King James is only periphery to the writing of Macbeth.

"But he's in the play," she says.

I chuckle. Yeah, James did consider Banquo his ancestor, I say.

"James is a character in the play," Sarah reiterates, earnestly holding me in a steady, clear-eyed gaze.

What in the world is she talking about? Then it hits me: in the witches' last apparition showing Banquo's lineage of kings, a specter holds up a mirror in which Macbeth sees King James. Scholars theorize that in the play's premiere at court, the king could see himself in the mirror.

"Oh my god, you're right!" I shout, jumping up and into a victory dance. What a perfect addition to our Macbeth menu! What a brilliant wife! God, I love this woman. "Bad brain day" my ass.

Friday, May 1, 2020—Better with Age

Sarah's glass is on one side of the table, mine on the other. I pour wine into her glass. I pour wine into mine.

Usually, I count as I pour. I do for hers but forget when I pour mine. I scoot my glass next to hers to compare.

Perfect. The level of wine is exactly the same. Truth be told, I've been pretty good at this lately, an acquired skill that I can only chalk up as luck, if not a second sense that comes with a couple of decades' worth of pouring wine.

"You're good," Sarah says.

"I am," I say. "I'm getting better with age. And don't you forget it."

"I won't forget it," she says.

Yes, she will, and soon. But I don't say that out loud.

Wednesday, May 6, 2020—A Blue Birthday

My birthdays pick at psychological scabs. I'm not keen on people making a fuss over me, but I always hope they do. When they do, I'm humbled and slightly uncomfortable. When they don't, I'm dejected and greatly discomforted.

It's only my birthdays I don't like. I make much over others' birthdays. My father would always sit across from the elevator at his assisted living center so he could greet everybody during shift change. For his last birthday on earth, I timed my seven-hour drive to Charlotte to step out of the elevator during shift change. "What are you doing here?!" he said in shock. Perfect.

Sarah's birthday is November 7, and from the dawn of our relationship, I've given her the commodity I value most: time. On November 1, I offer as her birthday gift the use of my time in whatever way she wants. She has seven days to tell me her wish and for me to bring her gift to fruition. I deviated from this tradition for her 60th birthday. I kidnapped her for a romantic oblivion getaway, but I couldn't surprise her with it because once when I did kidnap her for a romantic getaway, she stayed late at the office, ignoring her secretary's pleas to go home, and we almost didn't make our reservation. So, now, kidnap means not telling her where we're going. Not until we changed flights in Minneapolis did she find out we were heading to San Diego (an alternative, as a hurricane wiped out my initial bookings), and she didn't learn of the resort until I told the taxi driver.

Sarah has generally given my birthday scant notice. It either sneaks up on her or she takes at face value my desire to not be fussed over. This year, I decided to empower myself and plan big. In December, looking forward to our "Year of the Romance Passion," we decided to do another oblivion vacation in which I would kidnap her to the locale I originally planned for her 60th birthday (she never wanted me to reveal it in case we got such another opportunity). Not chancing the weather again and knowing my work schedule, we ruled out her birthday in November. Another emerging dilemma: constant caring for Sarah is one of my stress sources from which I could use a no-responsibilities break, but I don't want to do oblivion with anybody but Sarah. Thus, the earlier in the year the better, and the week of my birthday seemed perfect. I booked our trip.

It was work, not COVID-19 that initially intervened. The Commission shifted course, and suddenly my birthday landed in the middle of what was destined to be a tremendous crunch. Then, northern Virginia locked down and the destination shuttered due to the pandemic.

Still, I wanted to provide Sarah the opportunity to give me a special birthday, though I'd have to help her do it. On Monday, I broached it with her. She said she was working to get me something* and didn't need my help. Then she laid out my special day. "I want us to sleep in…"

"Stop right there," I said. I used to get up at 4:30 to beat the D.C. commute to my Commission office, and I've continued doing so though now teleworking. Those first three hours of the day, when I can focus solely on my work, have become something of a solace for me. "I want that time on my birthday, of all days," I told her. She accepted and continued: we'd shop at Wegmans together for a meal of my choosing which we would fix in the evening. Cool.

This morning, I get up with the 4:30 alarm. Lots of work to get done today, and I have a late morning telemeeting. I told Sarah last night we'd need to head to Wegmans by 8 a.m., so at 7, I wake her up and remind her we'd leave in an hour. She acknowledges, and I head back to my office downstairs. An hour later, Sarah is just getting up. Too late, I tell her, since I've got to be back at my desk in two hours for the meeting. She's disappointed, but I go alone. I'm disappointed, too. I gave her an hour's notice, but she chose to stay in bed, and the day's work is already crowding in.

On my way to Wegmans I work out a menu: chicken and yellow rice I learned from my dad and another longtime favorite, eggplant casserole that my mom's mother introduced me to when I was 14; for dessert, angel food cake with strawberries and whipped cream.

Wegmans has no whole chickens, and the yellow rice I want is out of stock. I at least get a nice eggplant. I finish the rest of my shopping before reconsidering my birthday meal, but upon returning to the meat counter, I see dozens of whole chickens. I grab three; it's my birthday, and that will be my plea if I'm questioned at checkout. I get a brand of yellow rice that neither I nor my dad ever used: how different can they be? I find the angel food cake with the strawberries, get through checkout with all three birds, and head home.

Sarah is sullen. I unpack the groceries by myself and get back to work. When it's time to fix dinner, Sarah doesn't come in to help. The meal itself is a dud: brands of yellow rice can be different, and this one hardly has any flavor. I screw up the eggplant casserole. The wine I choose is mediocre. The angel food cake is slightly stale.

Another birthday bust. For Sarah, too, which haunts me most. As I head to bed I'm slipping into a full-on depression. I desperately need a break—especially from my birthdays.

[*"Something" never materialized.]

Monday, May 11, 2020—Sonnet 77

The moment has come. I pick up a stack of 155 outdated business cards and draw the card at the top of the stack.

Back on January 1, I wrote a number on the back 154 of these cards and shuffled them, then wrote a large X on the back of the 155th card and put it at the bottom of the stack. Day by day, I pull from the top. When I arrive at the X card, I'll reshuffle the stack and start over.

Today's card bears the number 77. Picking up an illustrated book of William Shakespeare's sonnets on my desk, I turn to Sarah and announce, "Sonnet number 77: Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear."

Then I read:

Then I read:

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear,

Thy dial how thy precious minutes waste;

The vacant leaves thy mind's imprint will bear,

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste.

The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show

Of mouthed graves will give thee memory;

Thou by thy dial's shady stealth mayst know

Time's thievish progress to eternity.

Look, what thy memory can not contain

Commit to these waste blanks, and thou shalt find

Those children nursed, deliver'd from thy brain,

To take a new acquaintance of thy mind.

These offices, so oft as thou wilt look,

Shall profit thee and much enrich thy book.

I let this sink in. "Thus ends the daily reading of our Shakespearean sonnet," I intone. But we're both pretty gobsmacked.

That Shakespeare, looking over my shoulder, always.

* * *

On our walk today, Sarah points out a vanity license plate. The Washington Nationals curly W logo adorns the left side of the plate, and the letters spell "INEPUG." I try to aurally work out the puzzle: In E pug? Ine pug? I nep ug?

"Include the Nationals logo," Sarah says.

A moment. "Winepug?" Still makes no sense, so I Google "Winepug" and discover an impressive amount of bandwidth devoted to wine pugs, dogs that are both, respectively, connoisseurs and cute. That surprise doesn't bump the bigger moment: that Sarah easily grasped the license plate's puzzle. All her usually hampered cognitive skills—logical sequencing, contextual thinking, spatial understanding—suddenly firing on all cylinders.

Oh, that it could be I've suddenly awakened from a weird dream or we've lived through a giant misunderstanding. But I know it's just the wicked mystery that is the human mind. It's a moment I treasure nonetheless, not taking for granted its occurrence, as I would have five years ago; and not juxtaposing it with "time's thievish progress to eternity," as I've been wont to do lately. I take this new acquaintance of her mind and profit much.

Thursday, May 14, 2020—Temptation

Oh, the temptation is so great.

You know, I put up with a lot around here. I'm doing all the cleaning, all the cooking, all the finances, all the thinking. All of this on top of balancing, effectively, 2 1/2 jobs (which rises to three full-time jobs two months out of the year when I am supervising a magazine to publication). Sarah washes dishes, yes, but this morning I had to clean out two big pots just so I could get to the sink.

And though she has made trash and recycling management one of her tasks of habit, I had to get the trash out this morning. Second week in a row it fell on me because she didn't get up.

This morning I have to go to Wegmans. Sarah has said for two days she wants to go with me. Well, last week she wanted to go with me on my birthday, and she didn't get up even after I gave her an hour's notice. So here we are again: she's still in bed, and I've got to leave in an hour.

I should just let her stay in bed. Wait until I'm ready to leave, tell her I'm leaving, kiss her disappointed face, and lovingly assure her I'll be back as soon as I can. That will learn her. She wants to do things with me, get the hell up!

Oh, the temptation is so great. To show her that she needs to step up, to get up, to woman up, to colonel up. Though, in one respect, she certainly is womaning up. Even now I'm recalling our glorious moment last night, another in 30 years of such delectable moments. When my alarm went off at 4:30 this morning, I stayed in bed for another half hour just holding her.

Back to the temptation to teach her a lesson. She probably doesn't even remember we were going to go to Wegmans this morning. She doesn't know what day it is to remember the trash. She's had noticeable trouble tracking her days on the calendar the past two weeks. Punishing her for a condition she can't help? Demanding of her something she has no control over? Last week when she didn't get up in time to accompany me to Wegmans, she was probably as disappointed in herself as she was in me for not waiting another half hour for her to shower and dress (time I, in fact, didn't have to spare).

I go upstairs and turn on the hallway light as I enter the bedroom, a gentle wakeup if she's still asleep. I see her head lift off the pillow to look at me. I give her a one-hour, ten-minute notice (the duration of the Elton John CD I'm about to play as I work), and if she'd like to go with me, decide now, or sleep in. "After all," I remind her, "you have to get up early tomorrow" because we'll be fumigating the house before we go into my Commission office together. Sleeping in today could be more appealing to her, a temptation I grant would be worth her acquiescing to. She acknowledges her choice, and I head back to my desk downstairs. I get back to work, unaware if she got up but satisfied that she's now empowered, which she may or may not have been before I checked in on her.

A half hour later, she's standing next to my desk, ready to go. So much better than giving in to the temptation.

Thursday, May 21, 2020—The Ambush

She didn't cry. She didn't pout. She didn't sigh in resignation. No. Her face instead went to a place I've never been.

Last night, I forgot to monitor Sarah's pills. Stupid, stupid, stupid: that's one stupid for each pill I forgot to make sure she didn't forget to take. My biggest stupid, however, came this morning.

First, some background. Out of nowhere, Johns Hopkins called late last month to schedule Sarah for a PT Scan, the test our insurance provider, Tricare, had denied back in January. The doctor's appeal having apparently gone through, we set a May 8 date. On May 1, Johns Hopkins called to cancel: the test was denied again. I shot an irritable note off to Sarah's psychiatric neurologist, Dr. Muhammad Haroon Burhanullah. He calls us. He says he did appeal and thought he had explained the need for the test, but insurance will not cover PT Scans as a diagnostic tool for dementia. Dr. Burhanullah offers an option. Further studying Sarah's MRIs, he has concluded that rather than vascular dementia, she has Alzheimer's. Nevertheless, he couldn't rule out her seizures being a factor; that's why he wants to do the PT Scan. In order to get more leverage with Tricare, he suggests prescribing Donepezil, a pill that can slow memory regression.

However, Sarah had been taking Donepezil for 1 1/2 years before the seizures started. Her EEG tests at Johns Hopkins a year ago found that the Donepezil was, at least, exacerbating the seizures' effects. She was taken off the drug and put on a smaller dose of Keppra, and her epilepsy is now under control. After I explain this, Dr. Burhanullah suggests Memantine, similar to Donepezil but with less chance of seizure-causing side effects—his words. Seizures are a side effect of Donepezil? I didn't know that. After Sarah began taking it in 2016, I saw no improvement in her memory loss, but I did see rapid cognitive disintegration in tandem with the onset of seizures—and those may have been due to the Donepezil? I explain this new option to Sarah—we're on speaker phone with Dr. Burhanullah—and she chooses to proceed with the Memantine. Dr. Burhanullah prescribes one pill every evening for two weeks. Seeing no side effects, he doubled the dose, one pill in the evening and one in the morning along with the twice-daily doses of Keppra.

The three pills Sarah didn't take last night included her Keppra and Memantine. This morning, I tell her to take last night's cholesterol pill, and we'll put away the other two. I said this but didn't do it myself. Stupid. When you think it, do it, I've been telling her, preaching to the wrong person.

We're making our weekly Wegmans run this morning, she's dressed and ready to go. I check to see if she's taken her morning pills. She has. All three of last night's pills are missing, too. "Did you put those away?" I ask, pointing to the empty slot in her pill management box.

"I took them," she says.

I point to the empty morning slot. "You also took these?" She's not sure, and she's getting nervous.

I have to assume she has double-dosed both the Keppra (which has caused vertigo when she's done that before) and the Memantine (cousin to the seizure-causing Donepezil). "We can't risk it," I tell her. "I can't take you with me."

Sarah's face fills with frustration, anger, disappointment. Defeat. An anguish so deep she can't even cry. A maelstrom in her eyes, a trembling in her shoulders, she stands before me as the image of profound despair. I can't let that happen.

"This is my fault," I say. "I failed to monitor you closely." Anger flashes through her expression, aimed at me for sounding so patronizing or at herself, knowing that I'm ultimately not responsible for her failings. I hug her and feel her stiffen. I step back and see the slump of resignation in her shoulders. I'm losing this moment faster than I can think. "I can't leave you here alone, though," I say, stalling. She gives me a withering look: Oh, so she's ruined my day, too, this being my only opportunity to shop before the weekend.

"So, you can go with me," I say, "but you have to take great care, tell me immediately if you start feeling funny." She looks relieved. "I will," she says. I continue: "We'll stay together in case you start having trouble." She nods. I get stern. "You have to tell me if you start having any trouble so that I can get you to a seat."

"I promise," she says.

The shopping takes three times longer than I scheduled. I can't leave her in produce while I fetch other items. We shop not aisle by aisle but by priority needs in case she should falter. She makes it through without issue. She is happy. She is alive.

For me, this episode results in a discombobulating day. I don't recover the lost time nor the emotional stability I need to work efficiently. Still, I don't begrudge how upbeat Sarah is for the rest of the day. I don't ever want to see again her face cramped with such intense disappointment.

Does she grieve her inevitability as much as I do? She may not be fully aware of her memory loss, but this morning I saw the intensity of grief over her condition. My sense of helplessness is one of selfishness. Her sense of helplessness is a state of being, a state so anathema to the Sarah that hasn't given up on her former self.

When I broach this with her, she asks, "What grieving?" Is she being strong? Is she in denial? Is she that unaware of the extent of her condition? Am I wrong about everything? I can't answer these questions, nor need I. I can only take Sarah at face value, from moment to moment.

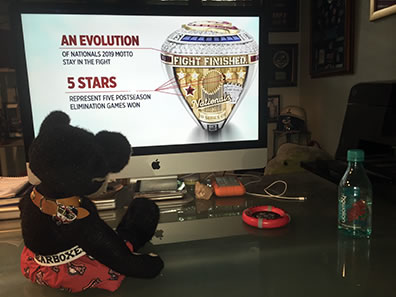

Sunday, May 24, 2020—Rings True

Tonight, the Washington Nationals unveil their World Series Championship ring. Sarah and I, along with Burlington, the Nationals' number one teddy bear fan, watch the program on my desktop computer.

Tonight, the Washington Nationals unveil their World Series Championship ring. Sarah and I, along with Burlington, the Nationals' number one teddy bear fan, watch the program on my desktop computer.

The ring's design is nicely done: simple, laden with jewels but not gaudy, and each jewel perfectly symbolic. The team's "Go 1-0 Every Day" motto is on the bottom of the ring, and Baby Shark is on the inside. After revealing the ring, the program switches to an interview with the manager, Davey Martinez, whose "Just go 1-0 today" mantra kept his players focused as they climbed out of a 19-31 start to the season all the way through the playoffs to the World Series title. Today, in fact, is the one-year anniversary of the team's 19-31 nadir; some around town want to make the date an annual holiday for its message of perseverance.

Martinez is doing the interview from his home, and hanging on the wall behind him is a sign that reads, "Today is always the best day."

It occurs to me that Sarah lives by that standard. She's has always had a positive attitude, except during a period in the Air Force when she was serving for a monster of a wing commander. Now, in these days of dementia, when her memory doesn't capture much of what happened yesterday and she has trouble tracking her tomorrows, she is pretty much forced to take every day on its own terms.

And she makes every day the best day ever. If the standard is "Go 1-0 Every Day," she's got a record of, oh, 142-3 so far this year. There's a standard we should all strive for.

From my 2015 review of Man of La Mancha at the Shakespeare Theatre Company, "It's All Merely Delusional":

"My first wife told people that I suffered from delusions of grandeur. She was right, and I still do. This website is ongoing self-incriminating testimony. Evidence A is how, in the aftermath of that first marriage crumbling, I deluded myself into thinking that a hot, intelligent, competent, professional woman named Sarah would ever give me the time of day, let alone like me, let alone want me, let alone love me, let alone marry me, let alone remain my wife for 23 years and, best I can tell, plans to continue being so for at least a couple more years. That has been one incredible delusion, but it's resulted in a life of grandeur, I can tell you that."